The likely proposal for the long-discussed special session seems to have settled, and its main feature would be to cut the top personal and corporate income tax rates. This disproportionately benefits the wealthy, and the corporate income tax cut will largely be captured by out-of-state shareholders, meaning the revenue will leave the state economy entirely. That increases the risk that, rather than inducing economic growth, the tax cuts will actually shrink the state economy.

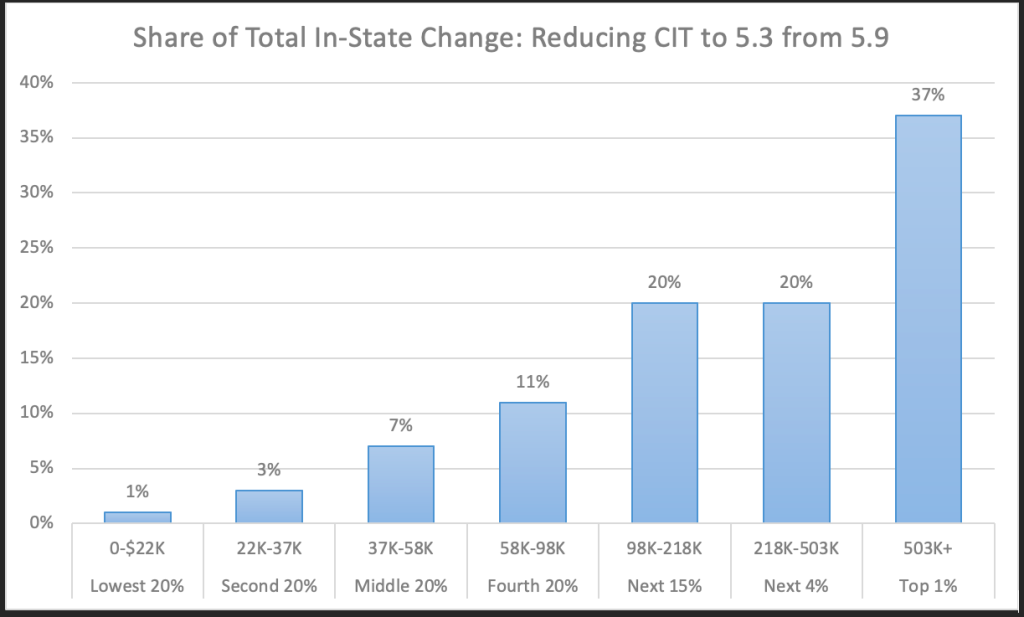

According to an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), nearly 80 percent of the corporate income tax cut in Arkansas would go to the top 20 percent of earners once fully phased in:

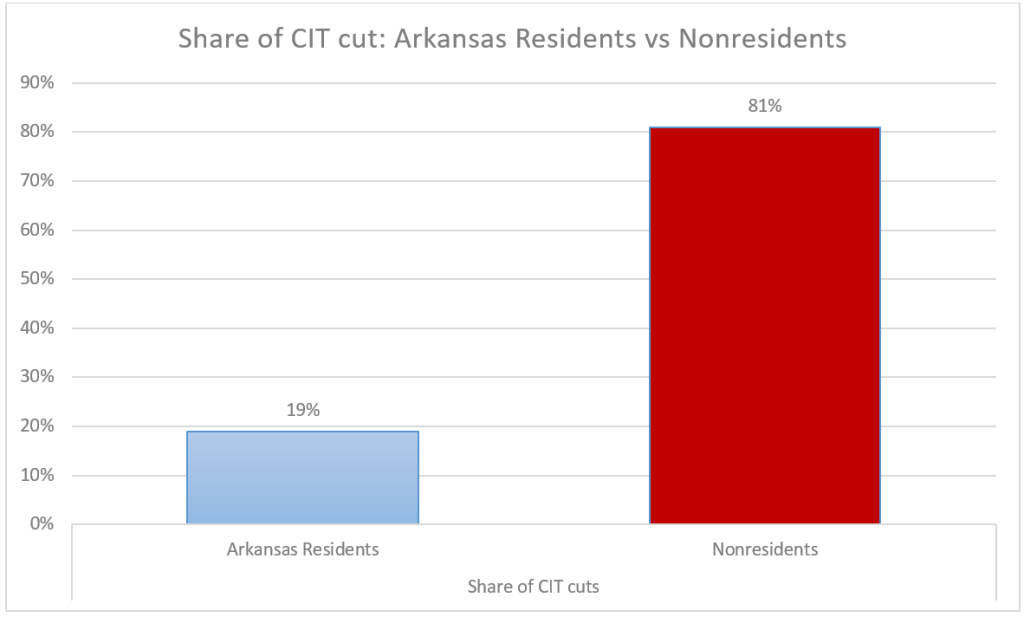

But even this underestimates the problem. ITEP estimates that this would cost $79 million in annual revenue, but only $15 million would go back to Arkansans at any income level. That means the vast majority of those who benefit from this tax cut won’t even live in Arkansas.

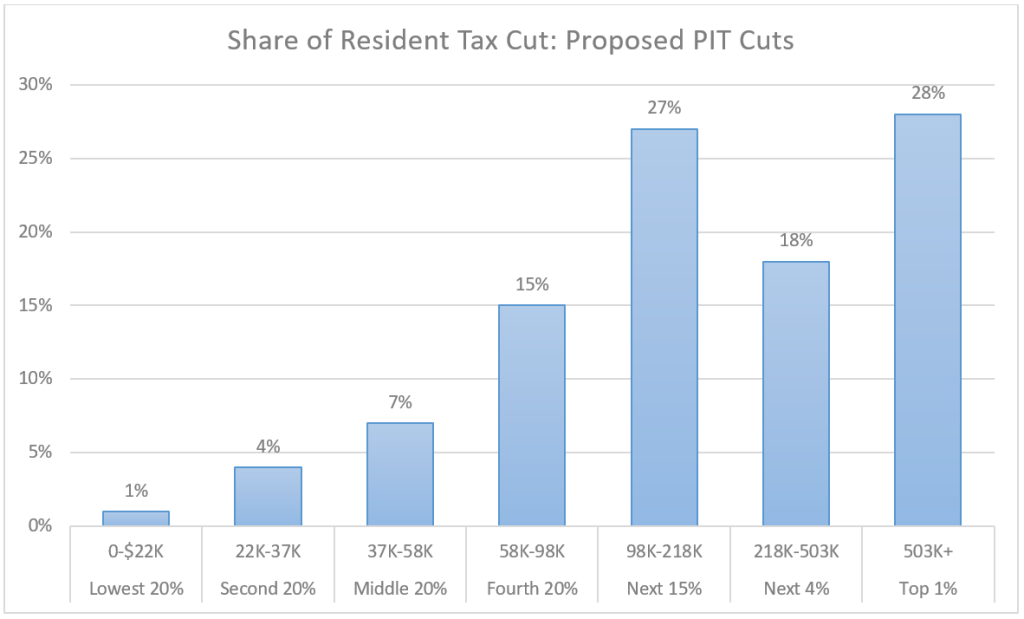

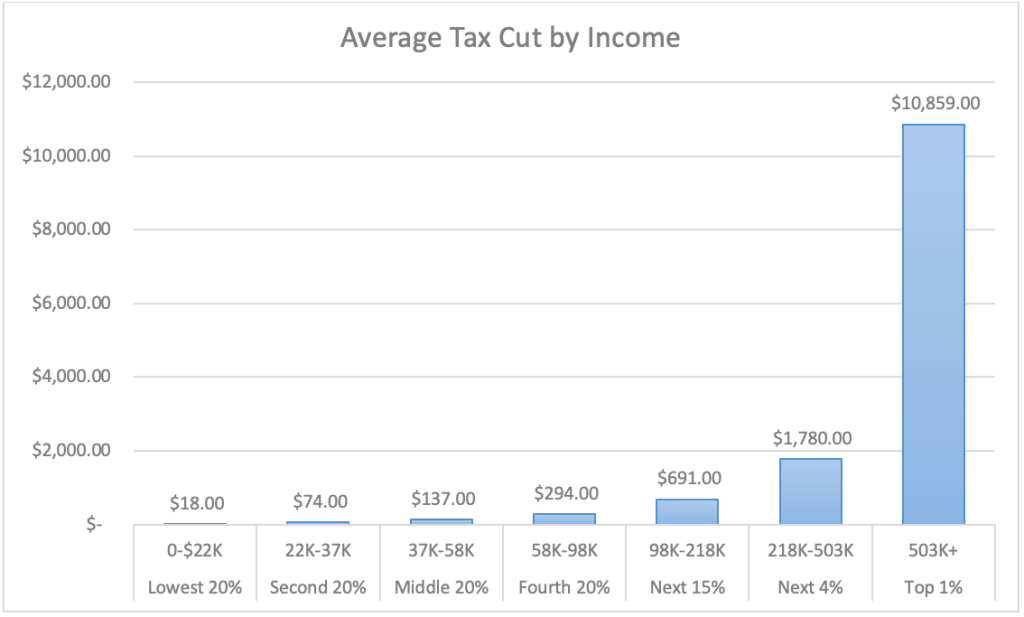

The proposal also includes some changes to reduce the number of tax tables in Arkansas from three to two, index the standard deduction to inflation, and create a new nonrefundable $60 tax credit for those whose taxable income is less than about $24,000. Supposedly this is to distribute some of the tax cut to lower-income Arkansans, but the cut to the top personal income tax rate is so deep that it overwhelms these changes:

Together these changes to our personal income tax rates would cost more than $520 million and the top 20 percent of earners in Arkansas would get 73 percent of the personal income tax cuts once fully phased in.

In exchange, the state economy might shrink or might grow less than one-tenth of one percent, depending on which of the legislature’s consultants you want to believe.

In 2018, the consultants for the Arkansas Tax Reform and Relief Legislative Task Force showed that any tax cuts would cause “output and job growth to turn negative” because they correctly inferred that a cut in state taxes necessitates a cut in state spending. That negative impact on jobs and output is because state spending creates jobs and induces economic growth, too. But even a more recent analysis, which explicitly ignored the impact of cuts on the state budget, only claims a minuscule benefit. They projected Arkansas’s “gross state product,” a measure of our economy, would increase by less than $1 billion over a decade. But Arkansas’s gross state product is more than $100 billion every year. That’s inducing economic growth by less than one-tenth of one-percent.

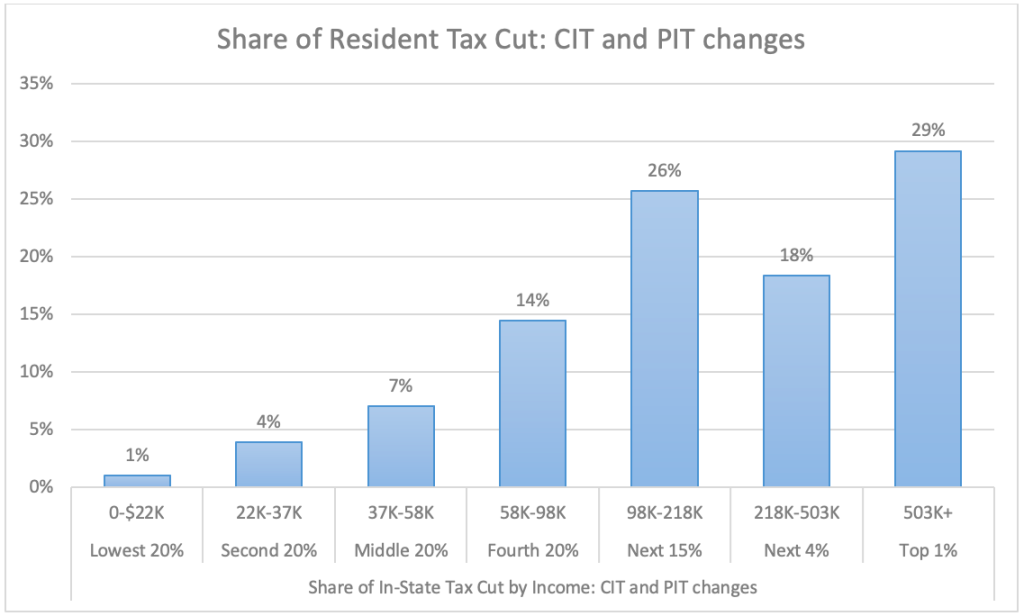

The combined personal and corporate income tax cuts would cost more than $600 million annually in ITEP’s estimates once fully phased in. That’s higher than official Department of Finance and Administration estimate of about $500 million once fully phased in by fiscal year 2026 because ITEP’s model assumes, based on recent history and empirical evidence, that incomes will continue to grow faster at the top of the income spectrum. Since those with the highest income will reap the biggest benefits, this has a big impact on the ultimate cost of the bill.

Put another way, ITEP estimates the average Arkansan in the top 1 percent – those making $503,000 or more – would see their taxes go down by more than $10,000. The average Arkansan in the bottom 20 percent – those making less than $22,000 – would see their taxes go down by less than $20.

And tens of millions of dollars would leave the state economy entirely to go into the pockets of corporate shareholders in other states. How much farther could that $600 million annually go if we instead made key investments to expand early education and child care, improve infrastructure, improve access to and the quality of health care, and other services to boost the state economy while helping children and families at the same time?