by Bruno Showers

Senior Policy Analyst

Introduction

At Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families, we work to ensure that all children have the resources and opportunities they need to realize their full potential. And what happens in a child’s early years is critical in determining their future success. The first years are especially important, as young children are discovering themselves and the world around them. The relationships children build in their first few months and years literally help shape their developing brains. The kind of healthy bonding that kids need to nurture their growing brains and reach their full potential requires consistent adult caregivers, whether parents or child care workers, to spend time with them when they’re very young. Parents face a real problem: the time when kids need attention and caregiving the most is also the time when parents need income the most. For most people, that means working outside the home. Unfortunately, young children are also expensive to care for. According to one estimate, the average annual cost for infant care in Arkansas is $6,890.

Most countries address this issue by having a policy mandating paid parental leave. Of the 41 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), only the United States lacks guaranteed paid parental leave. And while the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) guarantees up to 12 weeks of job-protected leave for new parents, this leave is unpaid. On top of that, more than 44 percent of private sector workers in the United States don’t qualify for FMLA protections. That’s because the FMLA requires workers to work a minimum number of hours, and employers to have 50 or more employees before those protections apply.

Recognizing how important bonding time is for child development, especially at very young ages, some states have begun to implement paid leave policies of their own. The method of financing paid family leave by the states that have implemented it is by creating a small payroll tax. These revenues go into a fund that eligible workers can draw from later, similar to insurance. Only eight states and Washington, D.C., in the United States guarantee paid parental leave of any kind for all workers. Some states, like Arkansas, have taken steps toward this goal by providing paid leave for state employees. And more than 50 municipalities nationwide have enacted paid family leave policies for municipal workers.

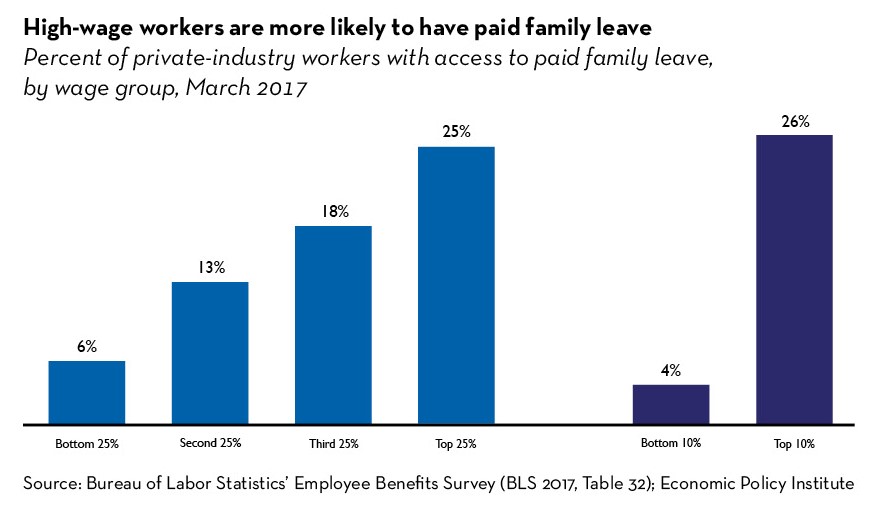

There were almost 4 million births in the United States in 2017, and almost 40,000 of those were in Arkansas. Despite efforts by states and localities to expand access, nationally only 14 percent of the civilian workforce had access to paid parental leave as an employment benefit in 2016, and women with lower education levels and lower wages were even less likely to have access. Women in the top 10 percent of the income distribution were more than six times as likely to have access to paid family leave as women in the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution.

The strong association between income and access to paid family leave means Black and Latino communities have the hardest choices when it comes to balancing caretaking and work. A legacy of institutional racism has caused people of color to suffer disproportionately from low wages and poverty; for example, Black households with children had a median income of $41,700 and Latino households with children had a median income of $49,100 in 2018, compared to $91,500 for White households with children.

Nationally, 11 percent of women without college degrees were fired, and 50 percent quit their jobs during pregnancy or shortly after childbirth. This loss of income places a financial hardship on families right when they need additional resources to ensure that their children grow up healthy and develop into their full potential. The lack of mandated paid family leave is burdensome, not only for families, but also on public resources — 21 percent of women who took unpaid FMLA leave reported having to go on public assistance in order to pay their bills.

Paid Sick Leave

A related issue is paid sick leave. Unlike paid family leave, which is often financed directly through payroll taxes, paid sick leave is generally mandated. Most states with mandatory sick leave policies require employers to offer sick leave on the basis of hours worked; for example, one hour of sick leave for every 40 hours worked, or one day of sick leave per month.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States was one of only two OECD countries without mandatory paid sick leave policies. Since the passage of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act in March, the United States now mandates paid leave, though these provisions only apply through December 31, 2020 and only for COVID-19 related health issues.

Though temporary, this mandated leave is in recognition of the public health crisis and the necessity — for the economy and for the public good — for people to stay at home to combat the spread of the virus. But many other countries were perhaps better situated to deal with the current pandemic because they already have mechanisms in place to deal with still serious “everyday” illnesses like the flu.

Outbreaks like COVID-19 sharply highlight that paid sick leave isn’t just about economic opportunity, but also about public health. While this coronavirus is new, research into the flu suggests that paid sick leave policies do help address public health problems — a study of U.S. states and cities that have enacted mandatory paid leave showed that sick pay mandates reduced the flu rate by as much as 40 percent.

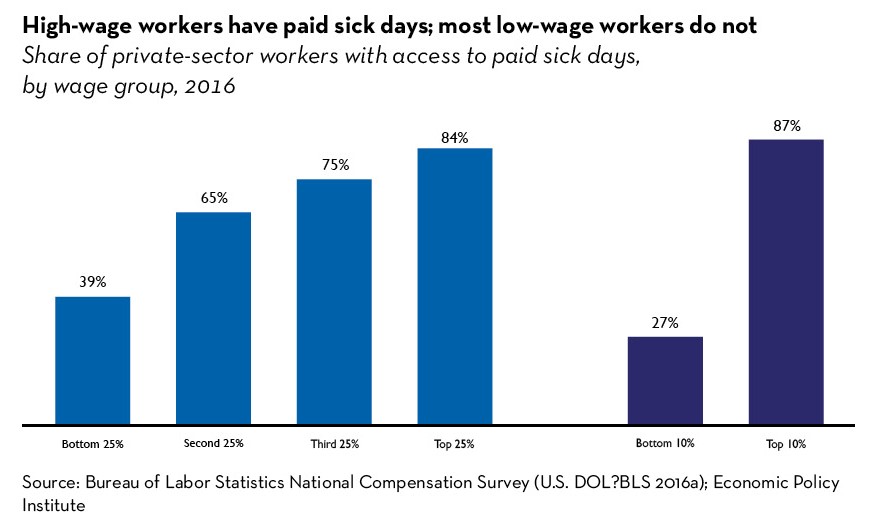

While 64 percent of private sector workers have access to paid sick leave, there are

vast disparities underlying these numbers.

Only about a quarter of the bottom 10 percent of earners have access to paid sick leave, while nearly all the top 10 percent of earners do. Policymakers should consider the current crisis an opportunity to create new rules to ensure every worker has access to basic policies that benefit the whole economy.

Infant Health Benefits

Children experience rapid neurological and nervous system development at very young ages. Children need to develop healthy brains and behaviors to reach their full potential, and this development relies on critical prosocial bonding with caregivers like their parents. Paid family leave is one important way that public policy can help promote this kind of healthy development so that children can grow into successful adults.

One way paid family leave can help promote this bonding is by increasing the rate and duration at which women breastfeed. Returning to work shortly after childbirth has been shown to reduce the likelihood of breastfeeding and increase the chance of early cessation of breastfeeding for working moms. Breastfeeding stimulates neurological and psychosocial development as well as improves a child’s immune system. Because it strengthens a child’s immune system, breastfeeding helps reduce the likelihood that children will develop a wide range of diseases and health complications, including but not limited to diabetes, asthma, and leukemia.

Another way that paid family leave policies promote healthy development is by increasing well-baby checkups and infant vaccination rates. Mothers who take time off from work after childbirth are more likely to take their children to well-baby checkups in the first years of their lives, and paid family leave policies help facilitate this. Children of mothers who take at least 12 weeks off after childbirth are much more likely to get all their recommended vaccinations.

The increase in breastfeeding from paid family leave, the increase in well visits and vaccinations, and the associated benefits may help explain why research suggests that paid family leave is also associated with lower overall infant mortality rates. Several multi-country studies have shown that paid family leave policies are associated with significantly reduced rates of infant mortality. It is important to note that the research suggests that unpaid leave does not have the same impact as paid leave — in fact, unpaid leave is not associated with a reduction in infant mortality at all.

Economic Benefits for Families

Paid family leave policies benefit new moms economically as well as in terms of health. Multiple studies have found that women with access to paid leave are more likely to work later into their pregnancy; and that, overall, women with access to paid leave are more likely to remain in the labor force than women without access to paid leave. Other research has found that offering paid family leave increases the number of hours that a woman works after returning to work.

Some research shows that paid family leave increases wages for women with children. One study found that women who report leaves of sufficient length are more likely to report wage increases in the year following the child’s birth than are women who take no leave at all. Another found that women with access to paid leave had higher wages than women without access to paid leave even after controlling for confounding factors like demographics and job characteristics.

The evidence suggests that this increase in work hours and wages is durable and persists long after the paid leave is taken. Research looking at California’s first-in-the-nation paid leave policies found that the implementation of paid family leave doubled the overall use of leave taking and that this was associated with an increase in work hours and wages for mothers of 1-to-3 year-olds.

Some research has even demonstrated long-term educational and economic benefits for children whose mothers take paid leave after childbirth. Research exploring the impact of the switch from mandated unpaid leave to paid leave in Norway found that children whose mothers had access to paid leave were more likely to complete high school and had higher wages than children whose mothers only had access to unpaid leave. This effect was even more pronounced for children whose mothers had lower levels of education, reinforcing the idea that women with lower income are disproportionately disadvantaged from leave policies that don’t include pay.

Costs and Benefits for the Overall Economy

One of the primary arguments against mandatory paid family leave policies is the potential negative impact they may have on businesses. However, evidence from states and countries that have mandated such policies has largely shown either no effect or even positive impacts.

One survey of businesses after the implementation of mandatory paid family leave in California found that 87 percent of employers indicated that paid family leave had not increased business costs, and 8.8 percent of firms reported that it had even resulted in cost savings because employees were able to use the paid family leave instead of employer-provided benefits, such as paid sick leave and vacation days.

Another way paid family leave policies help strengthen economic growth is by helping keep women in the workforce. Between 1990 and 2010 the United States fell from sixth to 17th among OECD countries in terms of women’s labor force participation rates, and the United States’ lack of paid family leave policies help to explain this drop. Lengthening the duration of paid family leave increases the labor force participation of younger women in particular.

Paid family leave policies may also help reduce reliance on public assistance. One study found that women who return to work after a paid leave have a 40 percent lower likelihood of receiving public assistance in the year following the child’s birth, when compared to those who return to work and take no leave at all. Men who return to work after taking paid family leave have a significantly lower likelihood of receiving public assistance and food stamps in the year following the child’s birth, when compared to those who return to work and take no family leave at all.

This patchwork of paid leave availability both exacerbates inequities for parents and creates inefficiencies in our economic system. That’s one reason some in the business community — especially small businesses — have begun to advocate for mandatory paid family leave policies. A national survey of small business executives conducted by the Bipartisan Policy Center showed the majority supports some form of paid family leave. Another survey by the industry association Small Business Majority showed that 70 percent of small businesses support establishing a national paid leave policy.

Financing Paid Leave Policies

The method of financing paid family leave by the states that have implemented it is by creating a small payroll tax. This is what is known as a “social insurance” approach, since these taxes are pooled into a fund used to administer benefits. This is like the “temporary disability” insurance programs run in some states; in fact, many states utilize this same system to administer paid family leave benefits, too. Payments are calculated based on a replacement rate of employee wages with a cap on maximum weekly benefits set at either a dollar amount or as a percent of statewide average weekly wages. These financing methods are essentially modeled on the Unemployment Insurance (UI) program, although UI is structured jointly by states and the federal government.

However, many policymakers who are otherwise supportive of paid family leave policies in the abstract are reluctant to impose new taxes — despite the benefits of paid family leave outlined above. The conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the more centrist Brookings Institution recently convened a working group to discuss various federal paid family leave proposals with the goal of finding common ground between conservative and liberal policymakers. They outline some elements of a compromise plan that they believe could be supported by both sides of the political aisle, notably:

- Any plan should be available to both mothers and fathers.

- Job protections must be included to ensure that parents aren’t discriminated against for taking advantage of paid leave.

Although the AEI-Brookings working group looked specifically at federal legislation, we believe these principles are good guidelines for state legislation, too.

Paid Family Leave Policies in Arkansas

During the 2017 legislative session, the Arkansas legislature passed SB 125, which was subsequently signed into law by Governor Hutchinson as Act 182. Act 182 amended the state government’s “Catastrophic Leave Bank Program,” which allowed certain state employees to claim catastrophic leave for medical purposes, to include maternity leave. The Catastrophic Leave Bank Program was a pool of accrued annual leave that is voluntarily donated by employees; Act 182 modified this so that employees could donate accrued sick leave in addition to annual leave.

State agencies — defined as all agencies, departments, boards, commissions, bureaus, council, or state-supported institutions of higher education — must participate in the catastrophic leave program, which is administered by the Office of Personnel Management in the Department of Finance and Administration.

The following governmental entities are exempt from the mandatory participation in the catastrophic leave program, but may choose to participate in the catastrophic leave program or stablish their own catastrophic leave bank:

- The General Assembly

- The Bureau of Legislative Research

- Arkansas Legislative Audit

- The Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department

- The Arkansas State Game and Fish Commission

- The Supreme Court

- The Court of Appeals

- The Administrative Office of the Courts

- A constitutional office

- Institutions of Higher Education

Employees of the participating agencies must meet certain criteria in order to qualify for maternity leave through this program. Only regular, benefits-eligible, full-time employees can participate. That employee must also have been employed full time for at least one year.

An eligible employee may receive up to four weeks of consecutive paid leave within the first 12 weeks after the birth of the employee’s biological child OR the placement of an adoptive child in the employee’s home.

Arkansas is one of at least 10 states to have adopted paid leave policies for state employees. Ideally, policymakers would explore options to finance a set of paid family leave policies that are available to workers statewide in any industry. As outlined above, nine states have achieved this through modest payroll taxes that are generally less than a one percent rate.

Barring that, paid family leave for state employees could be improved in several ways. First, as noted in our discussion above, paid leave policies have greater benefits for both parents and children if they are longer in duration. But Arkansas only provides four weeks of paid leave. Research suggests that for paid leave to promote healthy development for children it should be offered for at least 12 weeks and ideally longer.

Second, Arkansas only offers paid maternity leave. But paternity leave is just as meaningful for promoting healthy child development. Research shows that men with access to paid leave have a greater chance of being regularly involved in childcare activities like helping their children eat or putting their children to bed. And paternal engagement in these activities contributes to language skills and cognitive development. Finally, paid leave is only available for state agency employees who have worked for the state for at least one year, and many agencies may decide not to opt into the benefits. That means large swaths of the state workforce are potentially being excluded.

In order to expand the use and impact of paid family leave policies in Arkansas, we should: expand the duration of paid leave beyond four weeks; expand who is eligible to claim paid leave to include fathers as well as mothers; and the state should exempt fewer state agencies from participating in the program. At the minimum the state could at least commission a study to determine what the costs would be of implementing each of these changes — individually and in tandem.