Childhood Hunger is a Racial Equity Issue

There are far too many children in our country who go hungry every day, especially when we have the tools readily available to address childhood hunger. Instead of working to support children, our systems have been intentionally designed to place significant barriers on those who most need benefits. And the lasting result of that design is to ensure that children from Black, Indigenous and Other People of Color (BIPOC) families face hunger at much higher rates than their white counterparts.

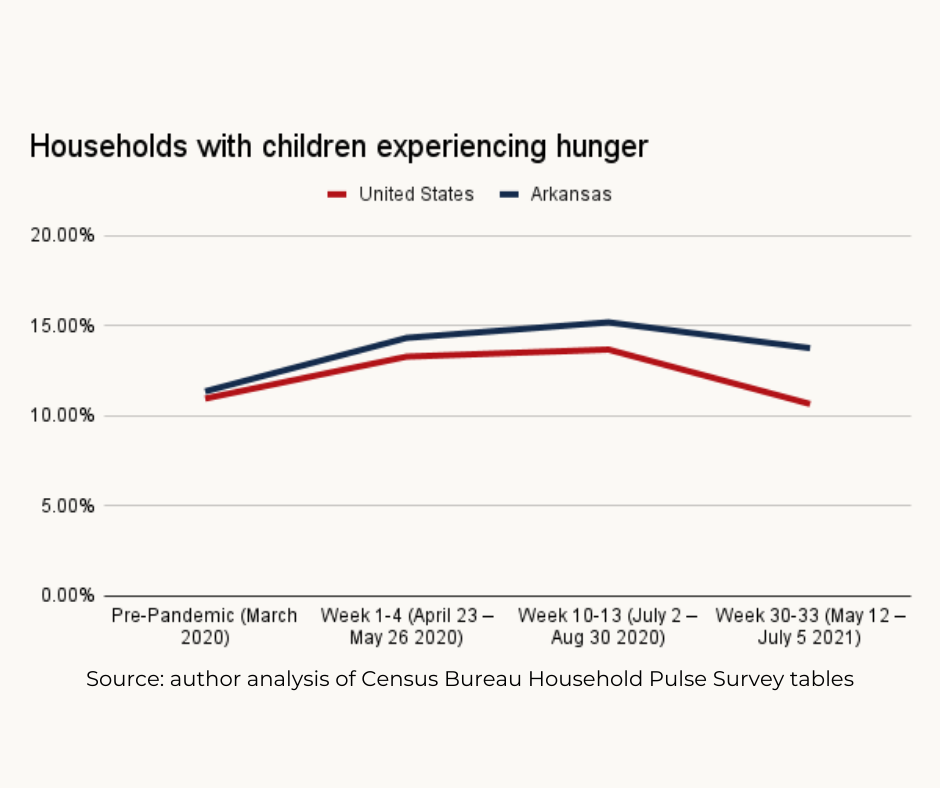

According to data from the Household Pulse Survey, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 11% of all households with children in the United States suffered food insufficiency, meaning that they sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat. That is nearly 11 million households with children. When the data are broken down, there are large disparities in the share of households experiencing food insufficiency by race and ethnicity.

See our new publication on Household Pulse Survey data and the Child Tax Credit in Arkansas.

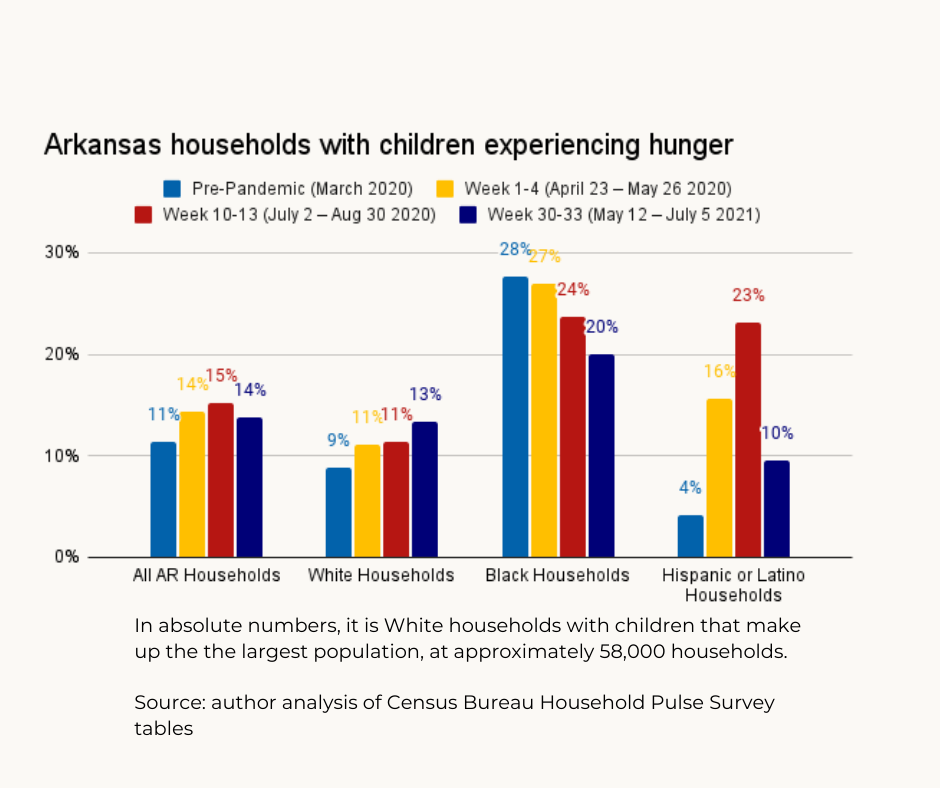

Household Pulse Survey data showed Arkansas with slightly more than 11% of all households with children in the state reporting that they were sometimes or often not able to get enough food to eat. But, while about 9 percent of White families with children had insufficient food, more than 27% of Black families with children were going hungry.

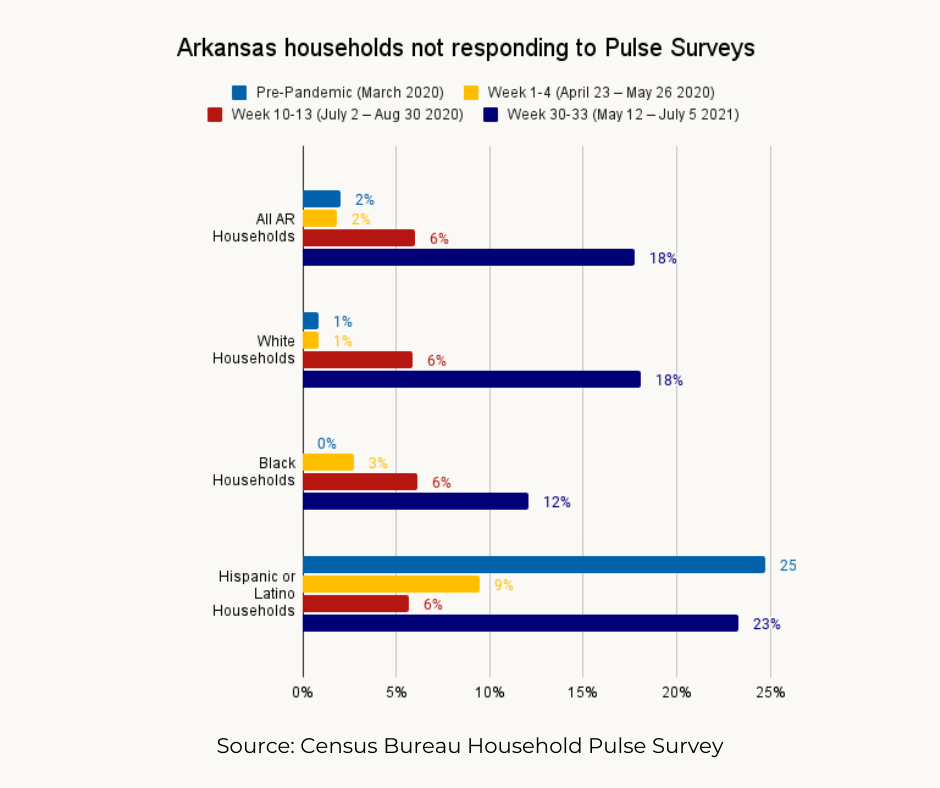

Because the Household Pulse Survey is intended to provide data quickly, rather than with an emphasis on accuracy, no in-person outreach or direct mail was used to solicit responses — only emails and text messages. The U.S. Census Bureau acknowledged this would lead to lower response rates. As a result, it appears that Latino or Hispanic households with children were not experiencing higher levels of hunger at certain times the data was collected, when it is likely that low response rates among Latino or Hispanic households with children masked the actual situation. Other potential issues with the data for Latino or Hispanic households with children could be the result of language barriers or failure to identify the household’s ethnicity as well as race.

The pandemic exacerbated child hunger in Arkansas, as it did many existing issues, and at the height of the pandemic in the summer of 2020, food insufficiency rates rose to about 11% of White households with children as compared to more than 23% for both Latino and Black households with children.

We know that the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected BIPOC families in Arkansas and nationwide, showcasing racial and social disparities that exist between different populations. While there are many factors that may contribute to these disparities, it is clear that equity, whether health, socioeconomic, education or otherwise still does not exist for BIPOC families.

When looking at child hunger, even when you control for socioeconomic, health, education, and other factors, racial disparities continue to exist. Thanks to continued research, it is becoming increasingly understood that structural racism is a significant factor in outcomes for children. Structural racism is “the normalization and legitimization of an array of dynamics – historical, cultural, institutional and interpersonal – that routinely advantage whites while producing cumulative and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color.” So, when evaluating structural racism in terms of hunger policy, we must look not only at the historical context, but also at the current norms that hold BIPOC communities at a disadvantage while over-advantaging Whites.

How Data is Used (or Not Used) to Disadvantage or Exclude Certain Groups

It is important to note here that one way that we disadvantage BIPOC communities is by failing to place importance on tracking their participation in programs, their outcomes, their specific needs, etc. For example, early on in the pandemic, it became clear from national data that COVID was disproportionately affecting Black and Brown people. Yet, Arkansas did not have race/ethnicity information on many Hispanic or Latino people. Why? Simply because they failed to capture that data. After being asked for data disaggregated by race and ethnicity, the state’s initial solution was to use the listed surnames to determine whether a COVID-positive individual was Hispanic or Latino. This is obviously not a scientific method of determining race/ethnicity.

White-centered data collection is not an issue specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather, the pandemic has highlighted these critical gaps in how we collect and analyze data. They are indicative of the many ways in which our state fails to track critical information for both state and federal programs that affect BIPOC communities.

Other clear examples of data-tracking deficiencies related to the issue of childhood hunger can be found in the way Arkansas tracks children in families living in poverty, children who lack enough food to eat some or all of the time, and children in families who receive public benefits. For 2019, the most recent year for which this data is available, we cannot find data available consistently across these indicators (as well as many others) for those children who are American Indian, Asian and Pacific Islander, or those who share two or more races. Finding where data on race and/or ethnicity is lacking in individual indicators of child well-being can be found on the Arkansas page of The Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center.

Missing or incomplete data is particularly significant for our Marshallese community. Northwest Arkansas has the largest population of Marshallese outside the Marshall Islands, with more than 12,000 Marshallese residents. Marshallese are allowed to come to the United States legally through a special provision called the “Compact of Free Association.” This agreement was put into place in recognition of the damage done to the Marshall Islands by U.S. nuclear testing both during and after World War II.

However, this special status comes with complications. On the one hand they can come to the United States and work legally, but they are ineligible for nearly all federal benefits because their special status is not the same as being a Lawful Permanent Resident (green card holder). Most programs require that a person is a U.S. Citizen or Legal Permanent Resident with more than five years living in the United States in that status. Since most Marshallese families are not eligible for that status, they do not participate in the many of the programs that generate the data used to track child well-being. Marshallese children fall under the racial category of Asian and Pacific Islanders, and there are only a few indicators where Arkansas has any data for that entire population, including Marshallese children. As a result, we are failing to track the well-being of Marshallese children, one of Arkansas’s most vulnerable populations.

Again, the Marshallese are only one example of poor data collection along racial and ethnic lines. At the state and federal level, we must do better tracking all racial and ethnic groups to ensure that we have information that tells the truth of the lives of children from BIPOC communities in Arkansas. These gaps in data from the groups that have been historically excluded from benefits allows for assumptions to be made — that they don’t use or need the programs that are available — when the truth is, these are the people most in need of services through our social safety net.

Applying the Racial Equity Lens to Hunger and SNAP

Let’s look at the largest federal anti-hunger program and third-largest anti-poverty program through the racial equity lens. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly Food Stamps and what many may know as the Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT). SNAP is demonstrably effective in reducing hunger and poverty and, therefore, reducing the effects of these issues on public health, education, etc. as well as boosting the economy. For every $1.00 invested in SNAP, there is a benefit to the economy of $1.50. In 2017, SNAP was responsible for helping lift 3.4 million people from poverty, and almost half of those were children.

The SNAP program was initially created and known as a Food Stamp program. For every $1.00 in stamps that a family purchased, the federal government provided $0.50 in stamps that could be used to purchase those commodities that farmers had in excess. The program as implemented in 1939 was temporary and was not particularly created to address hunger. Instead, the program was created as a means to help White farmers get rid of their surplus crops, and it benefited primarily White families that found themselves in need due to the Great Depression.

Black families in poverty were not the primary concern of policymakers because, for many Whites, they were considered “inherently unworthy.” This idea harkens back to the long-held belief dating back to slavery that Blacks were inherently lazy. Further, many rich Whites believed assistance should go to the “deserving poor,” or White families who had suddenly been impacted by the Great Depression.

Like the COVID-19 pandemic, the Great Depression affected Black people disproportionately. This was the height of the Jim Crow era, where state and local statutes explicitly legalized racial segregation with the purpose of denying Black people access to opportunities to the benefit of Whites. That meant that Black farmworkers were paid less or laid off. Sharecroppers were evicted by landlords, and in the cities any available jobs were seen as belonging to Whites as a right.

Later iterations of the Food Stamp Program brought us the idea of “welfare queens” in the 1980s, an idea intrinsically tied to Black women who were seen as taking advantage of the program. In the 1990s, under President Bill Clinton, SNAP became tightly tied to work through welfare reform. In December 2019, new and stricter work requirements for “able-bodied” adults without children ensured that 700,000 SNAP recipients would no longer be eligible for benefits. Recent debates on SNAP have focused on limiting what participants can buy using SNAP benefits because, by virtue of receiving SNAP benefits, participants are considered lacking the knowledge and ability to purchase the nutritious foods their families need.

A Focus on Exclusion Not Inclusion

Looking at these many changes to the SNAP program shows us that the main focus of legislation and rule changes has been targeted primarily not toward ensuring the alleviation of hunger, but instead on excluding as many people from the benefits as possible.

Although SNAP is a federal program, it is administered by the states. And states can restrict programs even more through laws and rules. The Arkansas Legislature has continued to do so to the detriment of Arkansas’s poor children and families. Arkansas has the strictest asset-limit cap of all the states. An asset limit requires that applicants for SNAP not only have very low income but also that any resources owned, such as property or money in bank accounts, are valued below the cap. Most states have eliminated asset limits or significantly raised them, with the understanding that programs like SNAP need to allow families to save money so they can transition off of SNAP and become more financially secure and less likely to fall back into poverty. Arkansas has limited assets to $2,250.00.

State-created restrictions became a serious problem as the pandemic hit, when many families who had never received SNAP benefits before found themselves suddenly in need of help affording food. To address the surge of food insecure families, Arkansas applied for many waivers from the federal government to allow greater access to the SNAP program. One example was not requiring face-to face-interviews prior to approval or recertification.

However, many of the waivers were not compliant with state law, leading Gov. Asa Hutchinson to declare that Arkansas would follow federal guidelines during the pandemic so that these benefits could be used by the thousands of Arkansans impacted by the pandemic. The governor’s actions were crucial in making sure that families could access necessary benefits at a faster rate and highlighted the unnecessary barriers our state laws have long imposed on SNAP recipients.

Even with waivers, and although SNAP could help lift many thousands out of poverty and reduce child hunger, many BIPOC families face challenges that actually or effectively make the program inaccessible. For example, Marshallese children are categorically ineligible for SNAP benefits. For others, the strict documentation requirements can be a challenge. For many rural participants who lack access to internet services, online applications are not accessible, and they may face transportation challenges in going to county offices to apply.

Further, while SNAP has just seen the largest increase in decades to benefit amounts due to changes in the Thrifty Food Plan, it is still a modest increase of $36.24 per person per month, or $1.19 per day. These changes, while important, still fail to address the needs of BIPOC communities. Nutritionists often dismiss many culturally relevant foods as not being “nutritional” and fail to understand how they can be part of a nutritious diet. Instead, we use “traditional” American foods as the ideal.

Using Equity as a Means to Ensure that All Families Facing Hunger Can Thrive

When we solve inequities impacting BIPOC families, all families will benefit. First, we must address the idea that poor people do not deserve to have the same healthy food as every other family. The inherent dignity of the person needs to be respected, and that includes the right to autonomy in making decisions about the best foods for their family.

Further we need to respect the wide variety of cultures that may have different diets than the “norm.” Different doesn’t mean unhealthy. Many cultures use a vast array of meats, fruits, vegetables, and spices that are often more expensive but are often healthier than a traditional American diet. We need to grant families “food sovereignty” so they can choose the best foods for their families, maximizing the nutrition, health, and cultural benefits of SNAP.

We need to specifically to address the issue of food deserts, where families cannot get quality foods because the stores they have access to don’t stock these items. For many families, food choice is an illusion. If there is only one store in a community that can accept SNAP benefits, recipients don’t have choices in what foods they access. They are restricted by what is offered.

Finally, we should eliminate barriers that make it hard for families to transition from poverty to financial stability. This includes removing the SNAP asset limits. This also includes dismantling the barriers keeping people from receiving benefits from multiple programs. Families who qualify should be able to receive wrap-around services, such as Women Infants and Children (WIC), Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), etc., without reducing food benefits.

Wrap-around services are critical to helping empower families to reach financial stability. Eliminating barriers and increasing access to food programs such as SNAP will not only help BIPOC families, who are disproportionately affected by poverty, but it will also help White families in poverty. In absolute numbers, White children are the largest population facing hunger in Arkansas. Of the approximately 106,000 households with children who were facing hunger in Arkansas prior to the pandemic, roughly 58,000 were White. More than half of the 160,000 Arkansas children in families that received public assistance in the form of SSI, cash public assistance, or SNAP in 2019 were White (83,000).

Implementing policy changes with the goal of achieving racial equity in outcomes doesn’t only ensure that BIPOC children will benefit; instead it ensures that the lives of all of Arkansas’s children will improve.