Editor’s note: The 2021 KIDS COUNT® Data Book is a 50-state report of recent household data developed by the Annie E. Casey Foundation analyzing how families have fared between the Great Recession and the COVID-19 crisis. Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families is Arkansas’s member of the national KIDS COUNT network.

Arkansas’s children reflect who we are as a state. Educating the next generation of Arkansans is one of our greatest responsibilities. But one disappointing finding for Arkansas in the 2021 KIDS COUNT® Data Book released this week was the state’s ranking on education. Based on 2019 data in this year’s report, Arkansas ranked 35th on education, down from 31st last year.

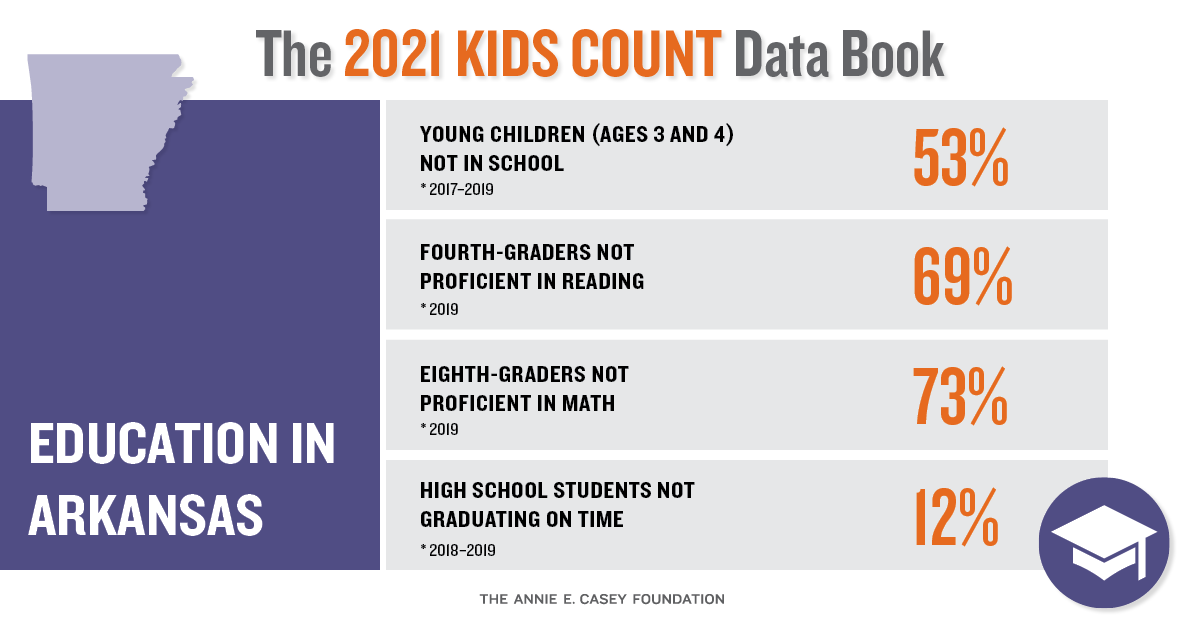

A key education indicator in the report is attendance in a pre-k program for 3- and 4-year-old children. More than half of Arkansas’s 3- and 4-year-old children (53 percent) attended a pre-K program in 2017-2019 —slightly worse than the national average (52 percent). Our ranking slid from 17th In last year’s report to 20th this year. Arkansas is only serving 1,000 more 3- and 4-year-olds than we did in 2011.

Arkansas used to be a national leader in access to quality preschool education, but our progress has stalled in recent years. One reason for our lack of progress has been flat state funding for the Arkansas Better Chance (ABC) pre-k program for more than a decade ($111-114 million annually since state fiscal year 2008). Meanwhile, many other states have doubled down on investing early and have passed Arkansas by in this area.

But attendance in a pre-k program for 3- and 4-year-old children is only part of the Arkansas early childhood picture. Many children receive services outside the ABC pre-k program through settings more commonly known as “childcare.” Recent data suggest the Arkansas childcare system is at a crossroads. A 2017 UAMS study found that the early childhood workforce in Arkansas faces high staff turnover, low wages, high levels of food and economic insecurity, and high levels of mental depression. These conditions, which were bad pre-pandemic, have likely only worsened during the pandemic.

Arkansas invests very little state funding in its early childhood workforce. Other than state funding for the ABC program, most early childhood funding in Arkansas comes from the federal level. Arkansas must immediately take steps to maintain and build the quality of and stability of the early childhood education workforce in the larger childcare system. Among the options:

- Improve the economic security of our early childhood education workforce, such as creating refundable tax credit for early childhood workers (or a state EITC for all low-income workers). Proposals to create a state tax credit for early childhood workers failed in 2019, and proposals to create a state EITC failed in both 2019 and 2021.

- Increase compensation for early childhood education workers in all government-funded programs serving children from birth to age 5. This compensation must be tied to improving the quality of the workforce. We need to reward workers with higher levels of education and those with more experience in the early childhood workforce.

- Allocate state funding for the T.E.A.C.H. (Teacher Education and Compensation Helps) program. T.E.A.C.H is an evidence-based program that helps build a skilled early childhood education workforce by providing scholarships and paid release time that enables early childhood educators to take coursework that leads to advanced credentials and degrees. T.E.A.C.H. upgrades the educational levels of workers by making advanced education more affordable, increasing wages, and reducing turnover.

- Do more to support family childcare programs. These are smaller programs typically run out of a provider’s home. In some areas, especially rural or more isolated areas, larger childcare centers or pre-k programs are not economically feasible, lack flexible care schedules, or are inaccessible due to transportation issues. In these cases, family childcare homes are the only option. These programs have been hit hard by the pandemic.

- Build the birth to age 3 system. Perhaps most importantly, we need to build the state’s system for serving infants and toddlers, a system that receives very little investment at the state level. This is where our efforts can have the biggest bang for the buck. The Excel by Eight Foundations Collaborative has developed a comprehensive agenda to promote early childhood development, and many of these recommendations are targeted to our youngest children. These should be read by every Arkansas policymaker.

Why is early childhood education and development so important? Research has long shown that children who receive quality early childhood education are better prepared for K-12 education and beyond. Quality early childhood education promotes early brain development and the social, emotional and cognitive development of young children. That’s why it’s so important to invest early in their learning and development. This is especially important for children living in poverty, who typically have fewer opportunities and resources to promote their development than do children in higher-income families. Quality early childhood education experiences are incredibly important to ensuring children have a strong start in life and can continue to gain ground socially and academically.

But building a solid foundation in the early years is only one piece of the education puzzle. Even when children have access to high-quality early childhood education, the foundation that has been built must be sustained through quality instruction in kindergarten and the later grades.

Reading proficiently by the end of third grade, for example, is a critical predictor of how well a child will perform in the later grades. In the latest Data Book, Arkansas is ranked 41st in the percent of fourth graders who can read proficiently at grade level. And 69 percent of Arkansas’s fourth graders are not reading at grade level, compared to 66 percent nationally.

Another key education indicator is basic math skills and numerical literacy. Eighth-grade math skills — particularly Algebra — are a good predictor of how prepared students are for the rigors of high school and post-secondary learning. On the latest NAEP highlighted in the Data Book, 73 percent of Arkansas’s eighth graders scored below proficient in math, compared to 67 percent nationally. Arkansas is ranked 43rd in the nation on this measure.

While these statistics are troubling on their own, there are major gaps in these outcomes for students of color, low-income children, and other groups such as those with special education needs. To close gaps in outcomes, we must target solutions to close equity gaps in resources and opportunities. The ability of these students to succeed in the later grades after building a solid early childhood foundation depends on a number of factors, such as adequately funding schools and having high-quality teachers, curriculum and methods of instruction, etc.

One issue that is often overlooked in discussions of success in the later grades is school discipline reform. Too many schools still rely on punitive disciplinary practices, such as expulsions and out-of-school suspensions, which disproportionately hurt students of color. We must do better at keeping kids in class and in school and keeping them out of the juvenile justice system and the school-to-prison pipeline. This means relying less on expulsions and out-of-school suspensions and more on approaches such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports and restorative justice, which are more effective in addressing school discipline issues.

In 2017 and 2019 Arkansas enacted limited bans on the use of expulsions, out-of-school suspensions, and corporal punishment in public schools. As a continued step in addressing these issues, AACF advocated for legislation in the 2021 legislative session that would have expanded the 2017 law that bans expulsions and out-of-school suspensions for kids in grades K-5. We tried but failed to convince the Arkansas legislature to expand that ban to at least include kids in foster care and special education students in grades 6-12. Another bill to expand a very limited ban on corporal punishment — which currently only applies for students the most severe developmental disabilities — was also defeated.

Finally, education in Arkansas must deal with the effects of the pandemic. Most experts believe that certain groups of students, including children of color, English language learners, and children with special education needs probably lost ground during the pandemic. Reasons why include differences in online access, access to digital devices, digital literacy of their parents, and the economic impacts of the pandemic on their families. The Arkansas Department of Education has contracted with the University of Arkansas to assess these gaps and determine how students fared during the pandemic. Arkansas policymakers must be prepared to act on that study when it is completed over the next year.