Editor’s note: The 2021 KIDS COUNT® Data Book is a 50-state report of recent household data developed by the Annie E. Casey Foundation analyzing how families have fared between the Great Recession and the COVID-19 crisis. Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families is Arkansas’s member of the national KIDS COUNT network.

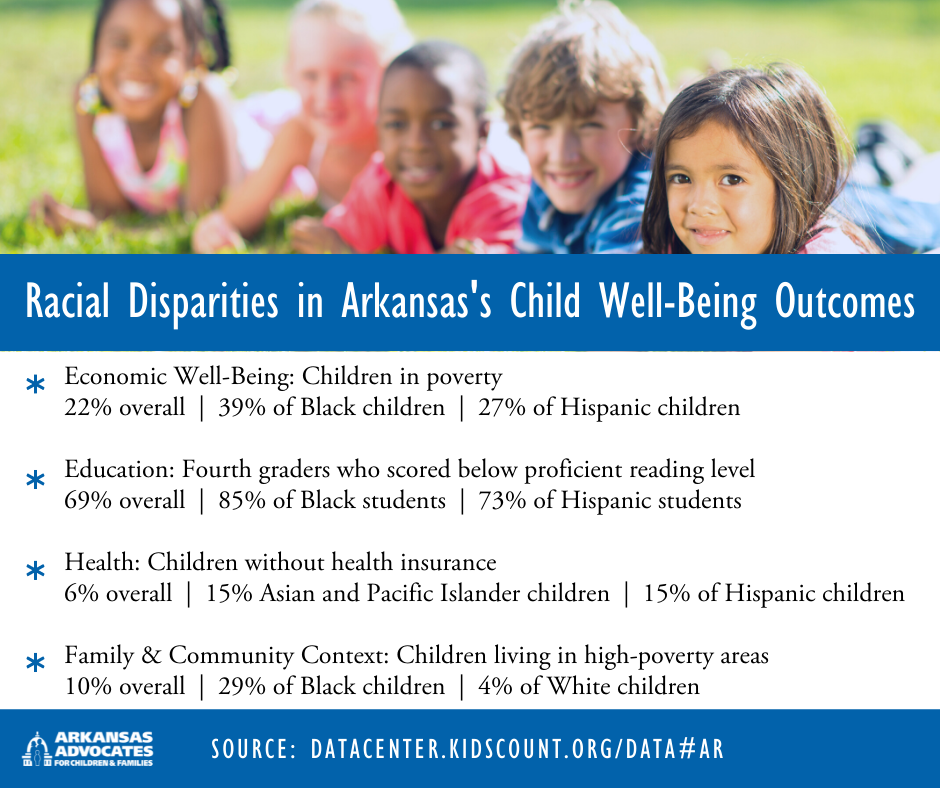

While the 2021 KIDS COUNT® Data Book does not have a category that specifically looks at racial equity, the KIDS COUNT Data Center provides many important child well-being indicators with data disaggregated by race. That means we can take a closer look to see how outcomes for Arkansas’s children differ by race. If we were to achieve racial equity, the percentage of Arkansas’s Black, Latino, and Asian and Pacific Islander (mostly Marshallese in Arkansas) children living in poverty would be no higher than the percentage of Arkansas’s White children.

The Data Book tracks children’s well-being across four domains and 16 indicators. Looking into the data underlying each of those indicators by race shows, over time, consistent lags for Black, Latino, and Marshallese children in Arkansas as compared to their White counterparts.

These are the very children that we know have been most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in Arkansas, so we must bear in mind that we do not yet know the full toll of the pandemic on these kids as the latest data is reflective of 2019.

In addition, it is important to note that the data is not complete, and this in itself demonstrates inequity for non-White children. All indicators track White children, but many of the indicators lack information on Arkansas’s American Indian and Asian children. The data used in the Data Book comes from both federal statistical agencies and state governments. At the state level, we must do better tracking all non-White groups to ensure that we have information that tells the full story of children from Black, Indian, and other People of Color (BIPOC) communities in Arkansas.

To be clear, not all indicators show Black, Latino, or Marshallese kids doing worse than their White counterparts. In some cases, one or more may be doing better. For example, for the indicator Children without Health Insurance, Black children are doing slightly better than their White counterparts (4% of Black children compared to 5% of White children). But in the long term, across all indicators, there are persistent patterns that show race/ethnicity is clearly a factor influencing kids’ well-being in Arkansas.

If there is one indicator that crosses through all domains in some way, it is Children in Poverty. In Arkansas, a shocking 22% of all children, or more than 1 in 5 children, live in poverty. That is absolutely unacceptable. However, by disaggregating the data by Race and Ethnicity, you find that the overall number is masking the high rates of poverty experienced by Black and Latino children. 39% of Black and 27% of Latino children live poverty, compared to 16% of White children.

The research on child poverty is clear. Children who live in poverty face more obstacles to success than children whose needs are met. Children who are born into poverty are most likely to experience a wide range of health problems, such as poor nutrition, chronic disease, mental illness, etc. They are likely to be food insecure, meaning they lack access to a reliable and enough affordable, nutritious food. This in turn also can cause educational challenges because kids are less likely to be able to concentrate and retain information.

We have been fighting the current iteration of the War on Poverty in this country for more than 57 years. And yet, poverty continues to win because we are not addressing the systemic and institutional racism that underlies all of our society. Failing to address systemic racism perpetuates the imbalance between BIPOC communities and their White counterparts. We must work toward rebuilding our social, economic, and government policies and practices that have in the past, and continue today, to perpetuate racial inequality and injustice. We need to stop thinking of this as a war that we can win and instead think about bold, evidence-based, inclusive, and comprehensive policies that can work together to end poverty.

The American Rescue Plan instituted one such policy this year by extending the Child Tax Credit by making it a near-universal, monthly child allowance. More than 88% of children are covered by this expansion nationally, and 94% of Arkansas’s children will benefit. However, this is a temporary credit. Making it permanent would be the single biggest effort to cut child poverty in the United State and would benefit 660,000 children in Arkansas.

Rather than budget cuts this fall, we should use the state’s so-called “surplus” and the one-time funds available from the American Rescue Plans for states and localities to improve the lives of BIPOC communities hardest hit by the pandemic. We can expand Medicaid to cover more families, increase SNAP access by eliminating income caps, increase access to quality early childcare programs as well as fully fund the out of school time programs for children, and expand childcare subsidies.

BIPOC communities need support now more than ever. We do ourselves and our state a disservice by pretending that everything is fine, and we’ve all recovered from the pandemic. We all know otherwise, so instead of pretending that everything is good, let’s invest in poor kids so that we can make sure that they have the same opportunities as other kids.