Too many corporations, especially those that operate in multiple states or countries, don’t pay their full share of Arkansas corporate income taxes. This is because, unlike more than half of other states, Arkansas has yet to protect itself from certain loopholes in our corporate tax law. This is eroding our state’s ability to pay for things like schools, parks, and roads, and is especially unjust to the small businesses that do pay full taxes on their profits.

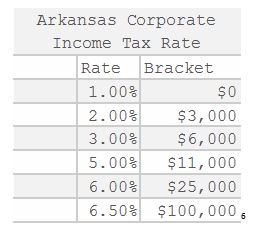

Taxing corporate income is not a new idea; the first federal corporate income tax was enacted in 1909, and Arkansas has had its own corporate income tax since 1929. This type of tax is also very common (44 states and the District of Columbia have their own corporate income tax). However, strategies to get around these taxes have evolved, while Arkansas tax law has not. The result is a weakening of our corporate tax structure, along with losses to state revenues.

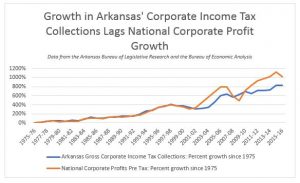

We can’t tell exactly how much money Arkansas loses because of tax loopholes, but one hint comes from looking at the change in nationwide corporate profits compared to Arkansas tax collections over time. When corporate profits increase, state corporate tax collections should go up in step. And indeed, that was the case from the 1970s to the early 2000s. During that time, Arkansas’s corporate income tax collections grew roughly on pace with national corporate profits. Since then, however, growth in our state corporate income tax collections has fallen far behind growth in corporate profits nationwide (the exception was during the recession).

Arkansas hasn’t decreased its corporate tax rate or made any other significant intentional policy changes that would account for such a large difference in growth between corporate profits and the taxes they pay to Arkansas. One likely explanation is the increasing prevalence of corporate tax avoidance and the failure of our tax laws to adapt.

Corporations that own related corporations in multiple states can use accounting techniques to “shift” profits to other states with lower corporate tax rates. So, even if a company has many facilities, employees, and customers in Arkansas, that business could still claim to earn little to no taxable “profit” in our state. This is known as interstate tax avoidance, and a similar practice can occur with companies operating in multiple countries.

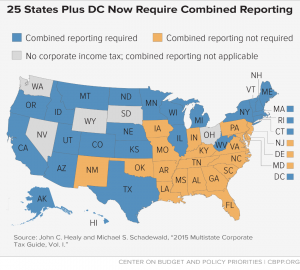

A common-sense policy change that could help correct this is Combined Reporting. Combined reporting requires companies to treat the parent company and its subsidiaries as one corporation for tax purposes. This rule eliminates many of the options for shifting corporate profits to other states with lower taxes, effectively nullifying interstate income shifting. By adding parent and subsidiary profits together before assigning a share of the combined profit to each state in which the corporate group is taxable (a process known as “apportionment,”) multi-state corporations cannot artificially move their profits to low- or no-tax states. Twenty-five of the 45 states with corporate income taxes (including DC) have seen the wisdom in upgrading their tax laws to require combined reporting.*

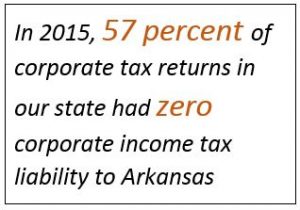

At present, many corporations operating in Arkansas are able to pay little to no corporate income tax to our state. In fact, most corporations that file in Arkansas don’t owe our state any corporate income tax at all.** In 2015, 57 percent of corporate tax returns in our state had zero corporate income tax liability to Arkansas.*** The lack of mandatory combined reporting likely contributes to this problem.

In a small state like Arkansas, many of those benefiting from corporations paying low or no corporate income taxes are affluent stockholders living in other states. It is reasonable to ask them to financially support the education services that create a skilled workforce and the roads and bridges that enable workers and raw materials to get in and finished products to get out. The only way to make sure that happens is by taxing the companies themselves through an effective corporate income tax.

There is strong evidence of public support for robust corporate taxation. According to a 2017 PEW poll, most Americans think corporations should pay more in taxes. That is twice as many people as those who say corporate taxes should be lowered. A 2017 poll found that “corporations not paying their fair share” is a top complaint about the tax system, with 62 percent saying that this fact bothers them “a lot.” Considering the recent windfall to corporations following the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, what better time to ask corporations to pay their share to our state?

Arkansas has an opportunity to improve our corporate tax system so that all businesses appropriately contribute to maintaining the economic structures they rely on. Combined reporting is a widely-adopted, common-sense way to modernize Arkansas’s tax system and make sure it keeps up with changes to our economy and how businesses operate.

*In addition, Texas levies a variant of a corporate income tax that also requires combined reporting.

**It is important to note, however, that all Arkansas corporations have to pay another tax, known as the “corporate franchise tax.” This is true even if they don’t owe any corporate income tax. Still, corporate franchise tax revenues are small compared to corporate income tax collections. In 2016, corporate franchise collections were about $24.5 million, while corporate income tax collections were about $519 million.

***Data from the Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration – Corporate Income Tax by NTI Range.